Three Initial Reactions From the 2023 Giro d'Italia Route Reveal

The newly-released route for the Italian grand tour teases a route built for time trial specialists, but the race will still likely to be won, and lost, in the mountains

The 2023 Giro d’Italia route was released this week, with the highlights centering around yet another mountain-loaded third week and a plethora of time trial kilometers. Make no mistake about it, while the end result is a very balanced and interesting route, the Giro’s organizer (RCS) created this edition with a heavy dose of uphill summit finishes and an above-average number of individual time trial kilometers to tempt Remco Evenepoel (or perhaps even Wout van Aert and/or Jonas Vingegaard) to eschew the Tour de France and instead head to the Italian grand tour in 2023.

While this decision by RCS is an admirable attempt to challenge the Tour de France’s dominance, which produces by far the most competitive GC field amongst the sport’s grand tours, it is likely to have little actual effect on Evenepoel’s decision. In fact, if Evenepoel does race the Giro in lieu of the Tour, it would be a mistake to do this due to 60+ kilometers of time trials on offer (for reasons outlined below) and should be due to an internal calculation at his QuickStep team that they don’t want to expend the resources to provide top-tier support at the sport’s biggest race.

2023 Giro d’Italia Route Overview:

It can be fun to use a newly released route to attempt to extrapolate the contenders and how the race will play out, but this exercise can end up being somewhat useless with the actual start being so far off since we lack a list of contenders and so much is likely to change over the course of seven months (i.e. last-minute rider transfers, off-season training crashes, illness, etc).

With that in mind, let’s take a big-picture look at the route and pull out three initial takeaways to keep in mind while looking at this course:

2023 Giro d’Italia Stage List

Stage 1: Fossacesia > Ortona (18.4km)-ITT

Stage 2: Teramo > San Salvo (204km)-flat

Stage 3: Vasto > Melfi (210km)-flat

Stage 4: Venosa > Lago Laceno (184km)-mountains (summit finish)

Stage 5: Atripalda > Salerno (172km)-hills

Stage 6: Naples > Naples (156km)-hills

Stage 7: Capua > Gran Sasso (218km)-mountains (summit finish)

Stage 8: Terni > Fossombrone (207km)-hills

Stage 9: Savignano sul Rubicone > Cesena (30.7km)-ITT

Rest Day #1

Stage 10: Scandiano > Viareggio (190km)-mountain

Stage 11: Camaiore > Tortona (218km)-flat

Stage 12: Bra > Rivoli (179km)-hills

Stage 13: Borgofranco d’Ivrea > Crans-Montana (208km)-mountains (summit finish)

Stage 14: Sierre > Cassano Magnago (194km)-mountain

Stage 15: Seregno > Bergamo (191km)-hills

Rest Day #2

Stage 16: Sabbio Chiese > Monte Bondone (198km)-mountains (summit finish)

Stage 17: Pergine Valsugana > Caorle (192km)-flat

Stage 18: Oderzo > Val di Zoldo (160km)-mountains (summit finish)

Stage 19: Longarone > Tre Cime di Lavaredo (182km)-mountains (summit finish)

Stage 20: Tarvisio > Monte Lussari (18.6km)-ITT

Stage 21: Rome > Rome (115km)-flat

Breakdown by Stage Type:

8 Mountain Stages

6 Summit Finishes

5Flat(ish) Stage

5 Hilly Stages

3 Individual Time Trials

67.7 total kms

9 climbing kms

1) The importance of TT kilometers is being vastly overrated

Due to coming in an era where most grand tours have attempted to decrease the number of time trials, the 60+ kilometers of individual time trials have grabbed plenty of headlines.

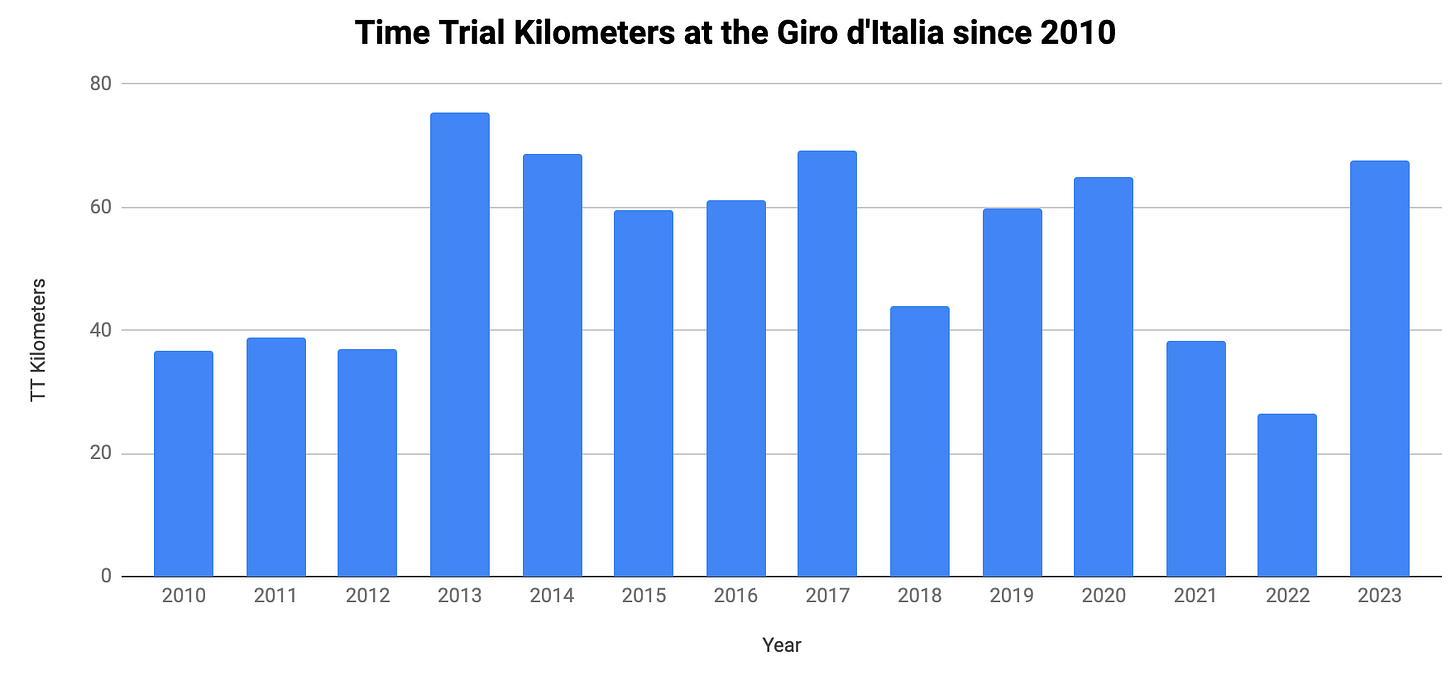

But, if we look back at the past few years, this Giro’s 67km of time trialing isn’t a massive outlier (the average since 2010 is 53km) and is in line with recent editions like 2017 and 2020 when it comes to individual kms against the clock.

In fact, over the last ten seasons, the Giro has averaged more TT kilometers per edition than either of the other two grand tours even while producing pure-climber winners more often than either the Tour or the Vuelta.

2) The mountains will be just as, if not more important, than the time trials

While everyone is preoccupied with the amount of time trialing kilometers, an arguably more important metric is the meters of vertical gain offered out on course.

The raw amount of vertical meters isn’t a perfect metric for the difficulty of the course, but it does serve as a decent outline for it. The 51,000 meters climbing on tap in 2023 means that anyone wanting to win the Giro will have to be as proficient at climbing as they are against the time trial and that winning will be far more complicated than stacking up time gains against the clock and limiting losses on the climbs (which pours cold water on any potential ‘Wout van Aert for GC’ campaigns’)

To help us quantify the difficulty of the route, I’ve created a ‘Course Difficulty Rating’ to produce a single number that tells us the relative importance of climbing vs time trialing (a higher number indicates a greater emphasis on climbing and a lower number indicates a greater emphasis on time trialing).

Past Winner List, Specialty & Course Difficulty Rating:

2010: Ivan Basso, pure climber, 11.4

2011: Alberto Contador, climber, 13.3

2012: Ryder Hesjedal, hybrid climber, 14.1

2013: Vincenzo Nibali, climber, 6.3

2014: Nairo Quintana, pure climber, 6.4

2015: Alberto Contador, climber, 8.6

2016: Vincenzo Nibali, pure climber, 7.5

2017: Tom Dumoulin, time trialist, 7.7

2018: Chris Froome, time trialist, 11.5

2019: Richard Carapaz, pure climber, 8.5

2020: Tao Geoghegan Hart, climber, 8.3

2021: Egan Bernal, climber, 12.2

2022: Jai Hindley, climber, 19.5

2023: ?, 7.5

With a ‘Course Difficulty Rating’ of 7.5, we can see that the 2023 route is tied for the 3rd most trial-focused route since 2010, but we can also see that there appears to be little-to-no correlation between number the time trial kilometers and the type of rider who goes on to win the race.

For example, the course with the second highest climbing to TT ratio on this list (2012), was won by Ryder Hesjedal, who wasn’t a pure climber, while the two lowest ratios, 2014/2015, were won by riders who are particularly bad time trialists (Vincenzo Nibali and Nairo Quintana).

3) The Giro is notoriously difficult to control and the 2023 edition will be no different

The main reason for the lack of time trialists winning at the Giro, despite it having more time trial kilometers than other grand tours, is the sheer uncontrolled nature of the racing at the Giro.

This is due to both the physically challenging nature of climbs in Italy and the fact that the overall depth of talent/fitness level in the field is far lower than the Tour de France (which tends to produce time trialist winners even with a small number of TT kilometers). This mix of harder climbs and less powerful peloton makes it extremely hard for large groups to stay together deep into major mountain stages and rewards riders who have the ability to attack from a long way out (i.e. Chris Froome in 2018).

All of this isn’t to say that Remco Evenepoel can’t win this race (and I’m still not convinced he is going to choose to do the Giro over the Tour), but that if he does, he will have to be extremely strong on both the climbs and time trials, while also racing with his head on a swivel to a degree that wasn’t required during his Vuelta victory, since multi-minute leads cultivated against the clock can be far more easily overturned at the ultra-chaotic Italian grand tour than the sport’s other three-week races.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Beyond the Peloton to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.